Building a Transparent Keyserver

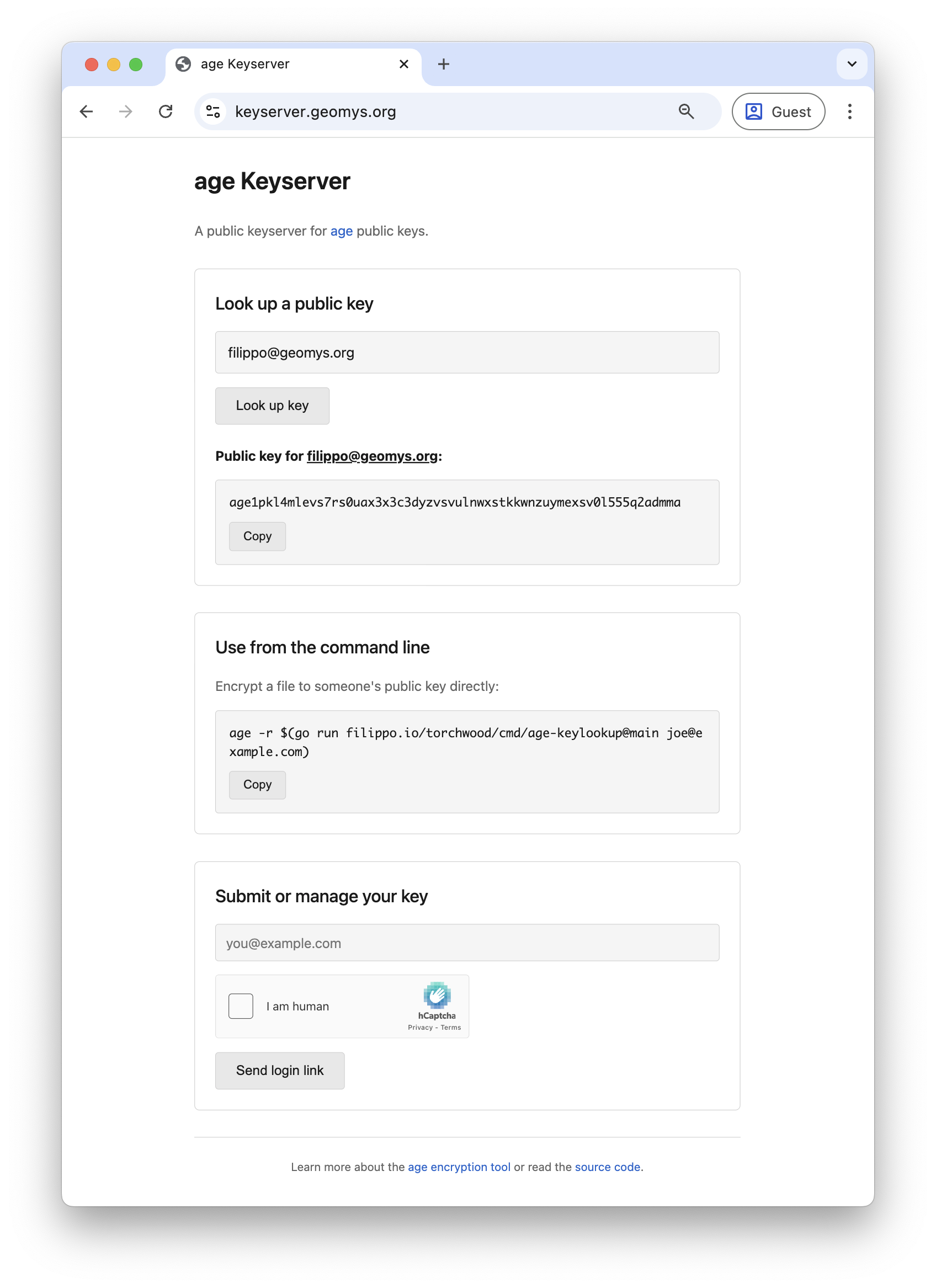

Today, we are going to build a keyserver to lookup age public keys. That part is boring. What’s interesting is that we’ll apply the same transparency log technology as the Go Checksum Database to keep the keyserver operator honest and unable to surreptitiously inject malicious keys, while still protecting user privacy and delivering a smooth UX. You can see the final result at keyserver.geomys.org. We’ll build it step-by-step, using modern tooling from the tlog ecosystem, integrating transparency in less than 500 lines.

I am extremely excited to write this post: it demonstrates how to use a technology that I strongly believe is key in protecting users and holding centralized services accountable, and it’s the result of years of effort by me, the TrustFabric team at Google, the Sigsum team at Glasklar, and many others.

This article is being cross-posted on the Transparency.dev Community Blog.

Let’s start by defining the goal: we want a secure and convenient way to fetch age public keys for other people and services.1

The easiest and most usable way to achieve that is to build a centralized keyserver: a web service where you log in with your email address to set your public key, and other people can look up public keys by email address.

Trusting the third party that operates the keyserver lets you solve identity, authentication, and spam by just delegating the responsibilities of checking email ownership and implementing rate limiting. The keyserver can send a link to the email address, and whoever receives it is authorized to manage the public key(s) bound to that address.

I had Claude Code build the base service, because it’s simple and not the interesting part of what we are doing today. There’s nothing special in the implementation: just a Go server, an SQLite database,2 a lookup API, a set API protected by a CAPTCHA that sends an email authentication link,3 and a Go CLI that calls the lookup API.

Transparency logs and accountability for centralized services

A lot of problems are shaped like this and are much more solvable with a trusted third party: PKIs, package registries, voting systems… Sometimes the trusted third party is encapsulated behind a level of indirection, and we talk about Certificate Authorities, but it’s the same concept.

Centralization is so appealing that even the OpenPGP ecosystem embraced it: after the SKS pool was killed by spam, a new OpenPGP keyserver was built which is just a centralized, email-authenticated database of public keys. Its FAQ claims they don’t wish to be a CA, but also explains they don’t support the (dubiously effective) Web-of-Trust at all, so effectively they can only act as a trusted third party.

The obvious downside of a trusted third party is, well, trust. You need to trust the operator, but also whoever will control the operator in the future, and also the operator’s security practices. That’s asking a lot, especially these days, and a malicious or compromised keyserver could provide fake public keys to targeted victims with little-to-no chance of detection.

Transparency logs are a technology for applying cryptographic accountability to centralized systems with no UX sacrifices.

A transparency log or tlog is an append-only, globally consistent list of entries, with efficient cryptographic proofs of inclusion and consistency. The log operator appends entries to the log, which can be tuples like (package, version, hash) or (email, public key). The clients verify an inclusion proof before accepting an entry, guaranteeing that the log operator will have to stand by that entry in perpetuity and to the whole world, with no way to hide it or disown it. As long as someone who can check the authenticity of the entry will eventually check (or “monitor”) the log, the client can trust that malfeasance will be caught.

Effectively, a tlog lets the log operator stake their reputation to borrow time for collective, potentially manual verification of the log’s entries. This is a middle-ground between impractical local verification mechanisms like the Web of Trust, and fully trusted mechanisms like centralized X.509 PKIs.

If you’d like a longer introduction, my Real World Crypto 2024 talk presents both the technical functioning and abstraction of modern transparency logs.

There is a whole ecosystem of interoperable tlog tools and publicly available infrastructure built around C2SP specifications. That’s what we are going to use today to add a tlog to our keyserver.

If you want to catch up with the tlog ecosystem, my 2025 Transparency.dev Summit Keynote maps out the tools, applications, and specifications.

tlogs vs Certificate Transparency vs Key Transparency

If you are familiar with Certificate Transparency, tlogs are derived from CT, but with a few major differences. Most importantly, there is no separate entry producer (in CT, the CAs) and log operator; moreover, clients check actual inclusion proofs instead of SCTs; finally, there are stronger split-view protections, as we will see below. The Static CT API and Sunlight CT log implementation were a first successful step in moving CT towards the tlog ecosystem, and a proposed design called Merkle Tree Certificates redesigns the WebPKI to have tlog-like and tlog-interoperable transparency.

In my experience, it’s best not to think about CT when learning about tlogs. A better production example of a tlog is the Go Checksum Database, where Google logs the module name, version, and hash for every module version observed by the Go Modules Proxy. The module fetches happen over regular HTTPS, so there is no publicly-verifiable proof of their authenticity. Instead, the central party appends every observation to the tlog, so that any misbehavior can be caught. The go get command verifies inclusion proofs for every module it downloads, protecting 100% of the ecosystem, without requiring module authors to manage keys.

Katie Hockman gave a great talk on the Go Checksum Database at GopherCon 2019.

You might also have heard of Key Transparency. KT is an overlapping technology that was deployed by Apple, WhatsApp, and Signal amongst others. It has similar goals, but picks different tradeoffs that involve significantly more complexity, in exchange for better privacy and scalability in some settings.

A tlog for our keyserver

Ok, so how do we apply a tlog to our email-based keyserver?

It’s pretty simple, and we can do it with a 250-line diff using Tessera and Torchwood. Tessera is a general-purpose tlog implementation library, which can be backed by object storage or a POSIX filesystem. For our keyserver, we’ll use the latter backend, which stores the whole tlog in a directory according to the c2sp.org/tlog-tiles specification.

s, err := note.NewSigner(os.Getenv("LOG_KEY"))

if err != nil {

log.Fatalln("failed to create checkpoint signer:", err)

}

v, err := torchwood.NewVerifierFromSigner(os.Getenv("LOG_KEY"))

if err != nil {

log.Fatalln("failed to create checkpoint verifier:", err)

}

policy := torchwood.ThresholdPolicy(2, torchwood.OriginPolicy(v.Name()),

torchwood.SingleVerifierPolicy(v))

driver, err := posix.New(ctx, posix.Config{

Path: *logPath,

})

if err != nil {

log.Fatalln("failed to create log storage driver:", err)

}

// Since this is a low-traffic but interactive server, disable batching to

// remove integration latency for the first request. Keep a 1s checkpoint

// interval not to hit the witnesses too often; this will be observed only

// if two requests come in quick succession. Finally, only publish a

// checkpoint once a day if there are no new entries, making the average qps

// on witnesses low. Poll for new checkpoints quickly since it should be

// just a read from a hot filesystem cache.

checkpointInterval := 1 * time.Second

if testing.Testing() {

checkpointInterval = 100 * time.Millisecond

}

appender, shutdown, logReader, err := tessera.NewAppender(ctx, driver, tessera.NewAppendOptions().

WithCheckpointSigner(s).

WithBatching(1, tessera.DefaultBatchMaxAge).

WithCheckpointInterval(checkpointInterval).

WithCheckpointRepublishInterval(24*time.Hour))

if err != nil {

log.Fatalln("failed to create log appender:", err)

}

defer shutdown(context.Background())

awaiter := tessera.NewPublicationAwaiter(ctx, logReader.ReadCheckpoint, 25*time.Millisecond)

Every time a user sets their key, we append an encoded (email, public key) entry to the tlog, and we store the tlog entry index in the database.

+ // Add to transparency log

+ if strings.ContainsAny(email, "\n") {

+ http.Error(w, "Invalid email format", http.StatusBadRequest)

+ return

+ }

+ entry := tessera.NewEntry(fmt.Appendf(nil, "%s\n%s\n", email, pubkey))

+ index, _, err := s.awaiter.Await(r.Context(), s.appender.Add(r.Context(), entry))

+ if err != nil {

+ http.Error(w, "Failed to add to transparency log", http.StatusInternalServerError)

+ log.Printf("transparency log error: %v", err)

+ return

+ }

+

// Store in database

- if err := s.storeKey(email, pubkey); err != nil {

+ if err := s.storeKey(email, pubkey, int64(index.Index)); err != nil {

http.Error(w, "Failed to store key", http.StatusInternalServerError)

log.Printf("database error: %v", err)

return

}

The lookup API produces a proof from the index and provides it to the client.

func (s *Server) makeSpicySignature(ctx context.Context, index int64) ([]byte, error) {

checkpoint, err := s.reader.ReadCheckpoint(ctx)

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to read checkpoint: %v", err)

}

c, _, err := torchwood.VerifyCheckpoint(checkpoint, s.policy)

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to parse checkpoint: %v", err)

}

p, err := tlog.ProveRecord(c.N, index, torchwood.TileHashReaderWithContext(

ctx, c.Tree, tesserax.NewTileReader(s.reader)))

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to create proof: %v", err)

}

return torchwood.FormatProof(index, p, checkpoint), nil

}

The proof follows the c2sp.org/tlog-proof specification. It looks like this

c2sp.org/tlog-proof@v1

index 1

CJdjppwZSa2A60oEpcdj/OFjVQyrkP3fu/Ot2r6smg0=

keyserver.geomys.org

2

HtFreYGe2VBtaf3Vf0AG0DAwEZ+H92HQqrx4dkrzk0U=

— keyserver.geomys.org FrMVCWmHnYfHReztLams2F3HUY6UMub3c5xu7+e8R8SAk9cxPKAB1fsQ6gFM16xwkvZ8p5aWaBf8km+M20eHErSfGwI=

and it combines a checkpoint (a signed snapshot of the log at a certain size), the index of the entry in the log, and a proof of inclusion of the entry in the checkpoint.

The client CLI receives the proof from the lookup API, checks the signature on the checkpoint from the built-in log public key, hashes the expected entry, and checks the inclusion proof for that hash and checkpoint. It can do all this without interacting further with the log.

vkey := os.Getenv("AGE_KEYSERVER_PUBKEY")

if vkey == "" {

vkey = defaultKeyserverPubkey

}

v, err := note.NewVerifier(vkey)

if err != nil {

fmt.Fprintf(os.Stderr, "Error: invalid keyserver public key: %v\n", err)

os.Exit(1)

}

policy := torchwood.ThresholdPolicy(2, torchwood.OriginPolicy(v.Name()),

torchwood.SingleVerifierPolicy(v))

// Verify spicy signature

entry := fmt.Appendf(nil, "%s\n%s\n", result.Email, result.Pubkey)

if err := torchwood.VerifyProof(policy, tlog.RecordHash(entry), []byte(result.Proof)); err != nil {

return "", fmt.Errorf("failed to verify key proof: %w", err)

}

If you squint, you can see that the proof is really a “fat signature” for the entry, which you verify with the log’s public key, just like you’d verify an Ed25519 or RSA signature for a message. I like to call them spicy signatures to stress how tlogs can be deployed anywhere you can deploy regular digital signatures.

Monitoring

What’s the point of all this though? The point is that anyone can look through the log to make sure the keyserver is not serving unauthorized keys for their email address! Indeed, just like backups are useless without restores and signatures are useless without verification, tlogs are useless without monitoring. That means we need to build tooling to monitor the log.

On the server side, it takes two lines of code, to expose the Tessera POSIX log directory.

// Serve tlog-tiles log

fs := http.StripPrefix("/tlog/", http.FileServer(http.Dir(*logPath)))

mux.Handle("GET /tlog/", fs)

On the client side, we add an -all flag to the CLI that reads all matching entries in the log.

func monitorLog(serverURL string, policy torchwood.Policy, email string) ([]string, error) {

f, err := torchwood.NewTileFetcher(serverURL+"/tlog", torchwood.WithUserAgent("age-keylookup/1.0"))

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to create tile fetcher: %w", err)

}

c, err := torchwood.NewClient(f)

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to create torchwood client: %w", err)

}

// Fetch and verify checkpoint

signedCheckpoint, err := f.ReadEndpoint(context.Background(), "checkpoint")

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to read checkpoint: %w", err)

}

checkpoint, _, err := torchwood.VerifyCheckpoint(signedCheckpoint, policy)

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("failed to parse checkpoint: %w", err)

}

// Fetch all entries up to the checkpoint size

var pubkeys []string

for i, entry := range c.AllEntries(context.Background(), checkpoint.Tree, 0) {

e, rest, ok := strings.Cut(string(entry), "\n")

if !ok {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("malformed log entry %d: %q", i, string(entry))

}

k, rest, ok := strings.Cut(rest, "\n")

if !ok || rest != "" {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("malformed log entry %d: %q", i, string(entry))

}

if e == email {

pubkeys = append(pubkeys, k)

}

}

if c.Err() != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("error fetching log entries: %w", c.Err())

}

return pubkeys, nil

}

To enable effective monitoring, we also normalize email addresses by trimming spaces and lowercasing them, since users are unlikely to monitor all the variations. We do it before sending the login link, so normalization can’t lead to impersonation.

// Normalize email

email = strings.TrimSpace(strings.ToLower(email))

A complete monitoring story would involve 3rd party services that monitor the log for you and email you if new keys are added, like gopherwatch and Source Spotter do for the Go Checksum Database, but the -all flag is a start.

The full change involves 5 files changed, 251 insertions(+), 6 deletions(-), plus tests, and includes a new keygen helper binary, the required database schema and help text and API changes, and web UI changes to show the proof.

Edit: the original patch series is missing freshness checks in monitor mode, to ensure the log is not hiding entries from monitors by serving them an old checkpoint. The easiest solution is checking the timestamp on witness cosignatures (+15 lines). You will learn about witness cosignatures below.

Privacy with VRFs

We created a problem by implementing this tlog, though: now all the email addresses of our users are public! While this is ok for module names in the Go Checksum Database, allowing email address enumeration in our keyserver is a non-starter for privacy and spam reasons.

We could hash the email addresses, but that would still allow offline brute-force attacks. The right tool for the job is a Verifiable Random Function. You can think of a VRF as a hash with a private and public key: only you can produce a hash value, using the private key, but anyone can check that it’s the correct (and unique) hash value, using the public key.

Overall, implementing VRFs takes less than 130 lines using the c2sp.org/vrf-r255 instantiation based on ristretto255, implemented by filippo.io/mostly-harmless/vrf-r255 (pending a more permanent location). Instead of the email address, we include the VRF hash in the log entry, and we save the VRF proof in the database.

+ // Compute VRF hash and proof

+ vrfProof := s.vrf.Prove([]byte(email))

+ vrfHash := base64.StdEncoding.EncodeToString(vrfProof.Hash())

+

// Add to transparency log

- entry := tessera.NewEntry(fmt.Appendf(nil, "%s\n%s\n", email, pubkey))

+ entry := tessera.NewEntry(fmt.Appendf(nil, "%s\n%s\n", vrfHash, pubkey))

index, _, err := s.awaiter.Await(r.Context(), s.appender.Add(r.Context(), entry))

if err != nil {

http.Error(w, "Failed to add to transparency log", http.StatusInternalServerError)

}

// [...]

// Store in database

- if err := s.storeKey(email, pubkey, int64(index.Index)); err != nil {

+ if err := s.storeKey(email, pubkey, int64(index.Index), vrfProof.Bytes()); err != nil {

http.Error(w, "Failed to store key", http.StatusInternalServerError)

log.Printf("database error: %v", err)

return

}

The tlog proof format has space for application-specific opaque extra data, so we can store the VRF proof there, to keep the tlog proof self-contained.

- return torchwood.FormatProof(index, p, checkpoint), nil

+ return torchwood.FormatProofWithExtraData(index, vrfProof, p, checkpoint), nil

In the client CLI, we extract the VRF hash from the tlog proof’s extra data and verify it’s the correct hash for the email address.

+ // Compute and verify VRF hash

+ vrfProofBytes, err := torchwood.ProofExtraData([]byte(result.Proof))

+ if err != nil {

+ return "", fmt.Errorf("failed to extract VRF proof: %w", err)

+ }

+ vrfProof, err := vrf.NewProof(vrfProofBytes)

+ if err != nil {

+ return "", fmt.Errorf("failed to parse VRF proof: %w", err)

+ }

+ vrfHash, err := vrfKey.Verify(vrfProof, []byte(email))

+ if err != nil {

+ return "", fmt.Errorf("failed to verify VRF proof: %w", err)

+ }

+

// Verify spicy signature

- entry := fmt.Appendf(nil, "%s\n%s\n", result.Email, result.Pubkey)

+ vrfHashB64 := base64.StdEncoding.EncodeToString(vrfHash)

+ entry := fmt.Appendf(nil, "%s\n%s\n", vrfHashB64, result.Pubkey)

if err := torchwood.VerifyProof(policy, tlog.RecordHash(entry), []byte(result.Proof)); err != nil {

return "", fmt.Errorf("failed to verify key proof: %w", err)

}

How do we do monitoring now, though? We need to add a new API that provides the VRF hash (and proof) for an email address.

mux.HandleFunc("GET /manage", srv.handleManage)

mux.HandleFunc("POST /setkey", srv.handleSetKey)

mux.HandleFunc("GET /api/lookup", srv.handleLookup)

+ mux.HandleFunc("GET /api/monitor", srv.handleMonitor)

mux.HandleFunc("POST /api/verify-token", srv.handleVerifyToken)

func (s *Server) handleMonitor(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

email := r.URL.Query().Get("email")

if email == "" {

http.Error(w, "Email parameter required", http.StatusBadRequest)

return

}

// Return as JSON

w.Header().Set("Content-Type", "application/json")

json.NewEncoder(w).Encode(map[string]any{

"email": email,

"vrf_proof": s.vrf.Prove([]byte(email)).Bytes(),

})

}

On the client side, we use that API to obtain the VRF proof, we verify it, and we look for the VRF hash in the log instead of looking for the email address.

Attackers can still enumerate email addresses by hitting the public lookup or monitor API, but they’ve always been able to do that: serving such a public API is the point of the keyserver! With VRFs, we restored the original status quo: enumeration requires brute-forcing the online, rate-limited API, instead of having a full list of email addresses in the tlog (or hashes that can be brute-forced offline).

VRFs have a further benefit: if a user requests to be deleted from the service, we can’t remove their entries from the tlog, but we can stop serving the VRF for their email address4 from the lookup and monitor APIs. This makes it impossible to obtain the key history for that user, or even to check if they ever used the keyserver, but doesn’t impact monitoring for other users.

The full change adding VRFs involves 3 files changed, 125 insertions(+), 13 deletions(-), plus tests.

Anti-poisoning

We have one last marginal risk to mitigate: since we can’t ever remove entries from the tlog, what if someone inserts some unsavory message in the log by smuggling it in as a public key, like age1llllllllllllllrustevangellsmstrlkef0rcellllllllllllq574n08?

Protecting against this risk is called anti-poisoning. The risk to our log is relatively small, public keys have to be Bech32-encoded and short, so an attacker can’t usefully embed images or malware. Still, it’s easy enough to neutralize it: instead of the public keys, we put their hashes in the tlog entry, keeping the original public keys in a new table in the database, and serving them as part of the monitor API.

// Compute VRF hash and proof

vrfProof := s.vrf.Prove([]byte(email))

- vrfHash := base64.StdEncoding.EncodeToString(vrfProof.Hash())

+

+ // Keep track of the unhashed key

+ if err := s.storeHistory(email, pubkey); err != nil {

+ http.Error(w, "Failed to store key history", http.StatusInternalServerError)

+ log.Printf("database error: %v", err)

+ return

+ }

// Add to transparency log

- entry := tessera.NewEntry(fmt.Appendf(nil, "%s\n%s\n", vrfHash, pubkey))

+ h := sha256.New()

+ h.Write([]byte(pubkey))

+ entry := tessera.NewEntry(h.Sum(vrfProof.Hash())) // vrf-r255(email) || SHA-256(pubkey)

index, _, err := s.awaiter.Await(r.Context(), s.appender.Add(r.Context(), entry))

It’s very important that we persist the original key in the database before adding the entry to the tlog. Losing the original key would be indistinguishable from refusing to provide a malicious key to monitors.

On the client side, to do a lookup we just hash the public key when verifying the inclusion proof. To monitor in -all mode, we match the hashes against the list of original public keys provided by the server through the monitor API.

var result struct {

Email string `json:"email"`

VRFProof []byte `json:"vrf_proof"`

+ History []string `json:"history"`

}

+ // Prepare map of hashes of historical keys

+ historyHashes := make(map[[32]byte]string)

+ for _, pk := range result.History {

+ h := sha256.Sum256([]byte(pk))

+ historyHashes[h] = pk

+ }

// Fetch all entries up to the checkpoint size

var pubkeys []string

for i, entry := range c.AllEntries(context.Background(), checkpoint.Tree, 0) {

- e, rest, ok := strings.Cut(string(entry), "\n")

- if !ok {

- return nil, fmt.Errorf("malformed log entry %d: %q", i, string(entry))

- }

- k, rest, ok := strings.Cut(rest, "\n")

- if !ok || rest != "" {

- return nil, fmt.Errorf("malformed log entry %d: %q", i, string(entry))

- }

- if e == base64.StdEncoding.EncodeToString(vrfHash) {

- pubkeys = append(pubkeys, k)

- }

+ if len(entry) != 64+32 {

+ return nil, fmt.Errorf("invalid entry size at index %d", i)

+ }

+ if !bytes.Equal(entry[:64], vrfHash) {

+ continue

+ }

+ pk, ok := historyHashes[([32]byte)(entry[64:])]

+ if !ok {

+ return nil, fmt.Errorf("found unknown public key hash in log at index %d", i)

+ }

+ pubkeys = append(pubkeys, pk)

}

Our final log entry format is vrf-r255(email) || SHA-256(pubkey). Designing the tlog entry is the most important part of deploying a tlog: it needs to include enough information to let monitors isolate all the entries relevant to them, but not enough information to pose privacy or poisoning threats.

The full change providing anti-poisoning involves 2 files changed, 93 insertions(+), 19 deletions(-), plus tests.

Non-equivocation and the Witness Network

We’re almost done! There’s still one thing to fix, and it used to be the hardest part.

To get the delayed, collective verification we need, all clients and monitors must see consistent views of the same log, where the log maintains its append-only property. This is called non-equivocation, or split-view protection. In other words, how do we stop the log operator from showing an inclusion proof for log A to a client, and then a different log B to the monitors?

Just like logging without a monitoring story is like signing without verification, logging without a non-equivocation story is just a complicated signature algorithm with no strong transparency properties.

This is the hard part because in the general case you can’t do it alone. Instead, the tlog ecosystem has the concept of witness cosigners: third-party operated services which cosign a checkpoint to attest that it is consistent with all the other checkpoints the witness observed for that log. Clients check these witness cosignatures to get assurance that—unless a quorum of witnesses is colluding with the log—they are not being presented a split-view of the log.

These witnesses are extremely efficient to operate: the log provides the O(log N) consistency proof when requesting a cosignature, and the witness only needs to store the O(1) latest checkpoint it observed. All the potentially intensive verification is deferred and delegated to monitors, which can be sure to have the same view as all clients thanks to the witness cosignatures.

This efficiency makes it possible to operate witnesses for free as public benefit infrastructure. The Witness Network collects public witnesses and maintains an open list of tlogs that the witnesses automatically configure.

For the Geomys instance of the keyserver, I generated a tlog key and then I sent a PR to the Witness Network to add the following lines to the testing log list.

vkey keyserver.geomys.org+16b31509+ARLJ+pmTj78HzTeBj04V+LVfB+GFAQyrg54CRIju7Nn8

qpd 1440

contact keyserver-tlog@geomys.org

This got my log configured in a handful of witnesses, from which I picked three to build the default keyserver witness policy.

log keyserver.geomys.org+16b31509+ARLJ+pmTj78HzTeBj04V+LVfB+GFAQyrg54CRIju7Nn8

witness TrustFabric transparency.dev/DEV:witness-little-garden+d8042a87+BCtusOxINQNUTN5Oj8HObRkh2yHf/MwYaGX4CPdiVEPM https://api.transparency.dev/dev/witness/little-garden/

witness Mullvad witness.stagemole.eu+67f7aea0+BEqSG3yu9YrmcM3BHvQYTxwFj3uSWakQepafafpUqklv https://witness.stagemole.eu/

witness Geomys witness.navigli.sunlight.geomys.org+a3e00fe2+BNy/co4C1Hn1p+INwJrfUlgz7W55dSZReusH/GhUhJ/G https://witness.navigli.sunlight.geomys.org/

group public 2 TrustFabric Mullvad Geomys

quorum public

The policy format is based on Sigsum’s policies, and it encodes the log’s public key and the witnesses’ public keys (for the clients) and submission URLs (for the log).

Tessera supports these policies directly. When minting a new checkpoint, it will reach out in parallel to all the witnesses, and return the checkpoint once it satisfies the policy. Configuration is trivial, and the added latency is minimal (less than one second).

+ witnessPolicy := defaultWitnessPolicy

+ if path := os.Getenv("LOG_WITNESS_POLICY"); path != "" {

+ witnessPolicy, err = os.ReadFile(path)

+ if err != nil {

+ log.Fatalln("failed to read witness policy file:", err)

+ }

+ }

+ witnesses, err := tessera.NewWitnessGroupFromPolicy(witnessPolicy)

+ if err != nil {

+ log.Fatalln("failed to create witness group from policy:", err)

+ }

// [...]

appender, shutdown, logReader, err := tessera.NewAppender(ctx, driver, tessera.NewAppendOptions().

WithCheckpointSigner(s).

WithBatching(1, tessera.DefaultBatchMaxAge).

WithCheckpointInterval(checkpointInterval).

- WithCheckpointRepublishInterval(24*time.Hour))

+ WithCheckpointRepublishInterval(24*time.Hour).

+ WithWitnesses(witnesses, nil))

On the client side, we can use Torchwood to parse the policy and use it directly with VerifyProof in place of the policy we were manually constructing from the log’s public key.

- vkey := os.Getenv("AGE_KEYSERVER_PUBKEY")

- if vkey == "" {

- vkey = defaultKeyserverPubkey

- }

+ policyBytes := defaultPolicy

+ if policyPath := os.Getenv("AGE_KEYSERVER_POLICY"); policyPath != "" {

+ p, err := os.ReadFile(policyPath)

+ if err != nil {

+ fmt.Fprintf(os.Stderr, "Error: failed to read policy file: %v\n", err)

+ os.Exit(1)

+ }

+ policyBytes = p

+ }

- v, err := note.NewVerifier(vkey)

- if err != nil {

- fmt.Fprintf(os.Stderr, "Error: invalid keyserver public key: %v\n", err)

- os.Exit(1)

- }

- policy := torchwood.ThresholdPolicy(2, torchwood.OriginPolicy(v.Name()), torchwood.SingleVerifierPolicy(v))

+ policy, err := torchwood.ParsePolicy(policyBytes)

+ if err != nil {

+ fmt.Fprintf(os.Stderr, "Error: invalid policy: %v\n", err)

+ os.Exit(1)

+ }

Again, if you squint you can see that just like tlog proofs are spicy signatures, the policy is a spicy public key. Verification is a deterministic, offline function that takes a policy/public key and a proof/signature, just like digital signature verification!

The policies are a DAG that can get complex to match even the strictest uptime requirements. For example, you can require 3 out of 10 witness operators to cosign a checkpoint, where each operator can use any 1 out of N witness instances to do so. Note however that in that case you will need to periodically provide to monitors all cosignatures from at least 8 out of 10 operators, to prevent split-views.

The full change implementing witnessing involves 5 files changed, 43 insertions(+), 11 deletions(-), plus tests.

Summing up

We started with a simple centralized email-authenticated5 keyserver, and we turned it into a transparent, privacy-preserving, anti-poisoning, and witness-cosigned service.

We did that in four small steps using Tessera, Torchwood, and various C2SP specifications.

cmd/age-keyserver: add transparency log of stored keys

5 files changed, 259 insertions(+), 8 deletions(-)

cmd/age-keyserver: use VRFs to hide emails in the log

3 files changed, 125 insertions(+), 13 deletions(-)

cmd/age-keyserver: hash age public key to prevent log poisoning

2 files changed, 93 insertions(+), 19 deletions(-)

cmd/age-keyserver: add witness cosigning to prevent split-views

5 files changed, 43 insertions(+), 11 deletions(-)

Overall, it took less than 500 lines.

7 files changed, 472 insertions(+), 9 deletions(-)

The UX is completely unchanged: there are no keys for users to manage, and the web UI and CLI work exactly like they did before. The only difference is the new -all functionality of the CLI, which allows holding the log operator accountable for all the public keys it could ever have presented for an email address.

The result is deployed live at keyserver.geomys.org.

Future work: efficient monitoring and revocation

This tlog system still has two limitations:

-

To monitor the log, the monitor needs to download it all. This is probably fine for our little keyserver, and even for the Go Checksum Database, but it’s a scaling problem for the Certificate Transparency / Merkle Tree Certificates ecosystem.

-

The inclusion proof guarantees that the public key is in the log, not that it’s the latest entry in the log for that email address. Similarly, the Go Checksum Database can’t efficiently prove the Go Modules Proxy

/listresponse is complete.

We are working on a design called Verifiable Indexes which plugs on top of a tlog to provide verifiable indexes or even map-reduce operations over the log entries. We expect VI to be production-ready before the end of 2026, while everything above is ready today.

Even without VI, the tlog provides strong accountability for our keyserver, enabling a secure UX that would have simply not been possible without transparency.

I hope this step-by-step demo will help you apply tlogs to your own systems. If you need help, you can join the Transparency.dev Slack. You might also want to follow me on Bluesky at @filippo.abyssdomain.expert or on Mastodon at @filippo@abyssdomain.expert.

The picture

Growing up, I used to drive my motorcycle around the hills near my hometown, trying to reach churches I could spot from hilltops. This was one of my favorite spots.

Geomys, my Go open source maintenance organization, is funded by Smallstep, Ava Labs, Teleport, Tailscale, and Sentry. Through our retainer contracts they ensure the sustainability and reliability of our open source maintenance work and get a direct line to my expertise and that of the other Geomys maintainers. (Learn more in the Geomys announcement.)

Here are a few words from some of them!

Teleport — For the past five years, attacks and compromises have been shifting from traditional malware and security breaches to identifying and compromising valid user accounts and credentials with social engineering, credential theft, or phishing. Teleport Identity is designed to eliminate weak access patterns through access monitoring, minimize attack surface with access requests, and purge unused permissions via mandatory access reviews.

Ava Labs — We at Ava Labs, maintainer of AvalancheGo (the most widely used client for interacting with the Avalanche Network), believe the sustainable maintenance and development of open source cryptographic protocols is critical to the broad adoption of blockchain technology. We are proud to support this necessary and impactful work through our ongoing sponsorship of Filippo and his team.

-

age is not really meant to encrypt messages to strangers, nor does it encourage long-term keys. Instead, keys are simple strings that can be exchanged easily through any semi-trusted (i.e. safe against active attackers) channel. Still, a keyserver could be useful in some cases, and it will serve as a decent example for what we are doing today. ↩

-

I like to use the SQLite built-in JSON support as a simple document database, to avoid tedious table migrations when adding columns. ↩

-

Ok, one thing is special, but it doesn’t have anything to do with transparency. I strongly prefer email magic links that authenticate your original tab, where you have your browsing session history, instead of making you continue in the new tab you open from the email. However, intermediating that flow via a server introduces a phishing risk: if you click the link you risk authenticating the attacker’s session. This implementation uses the JavaScript Broadcast Channel API to pass the auth token locally to the original tab, if it’s open in the same browser, and otherwise authenticates the new tab. Another advantage of this approach is that there are no authentication cookies. ↩

-

Someone who stored the VRF for that email address could continue to match the tlog entries, but since we won’t be adding any new entries to the tlog for that email address, they can’t learn anything they didn’t already know. ↩

-

Something cool about tlogs is that they are often agnostic to the mechanism by which entries are added to the log. For example, instead of email identities and verification we could have used OIDC identities, with our centralized server checking OIDC bearer tokens, held accountable by the tlog. Everything would have worked exactly the same. ↩